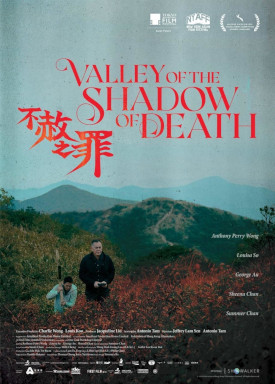

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Valley Of The Shadow Of Death (2024) Film Review

Valley Of The Shadow Of Death

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

Questions of culpability, will and belief echo around Sen Lam and Antonio Tam’s uneasy drama, which premièred at the 2024 Tokyo International Film Festival. It is blunt in setting up its central scenario, but complexities emerge which muddy the waters and trouble the emotional logic of its characters . Morality in the real world is rarely pure.

Paul Leung (Anthony Chau-Sang Wong) is a pastor in small Hong Kong Baptist sect the Church of Faith and Love. Devoted to his congregation, he speaks about the importance of bringing people into the church to save them from sin, and of setting aside one’s own judgement to let God’s take precedence. He also talks about the way that faith can be influenced by pain – something that he knows a lot about because, three years ago, he and his wife (Louisa So) lost their teenage daughter Ching (Sheena Chan) to suicide. They place the blame for this squarely on the shoulders of a former schoolmate of hers, Chan (George Au), which is not unreasonable, given what he did to her. When Chan gets out of prison and is brought into the church by one of Leung’s assistants, initially unaware of who Leung is, the pastor’s ability to stick to his principles is tested to the extreme.

The role of Chan is a brave choice for Au, a pop star with a fairly clean cut image, but it enables him to demonstrate that he’s serious about acting, giving him plenty to wrestle with. He handles it pretty well, and his innocent appearance helps persuade viewers to restrain their own judgement even though it’s not difficult to guess what Chan did. Three years is a long time at that age so it seems possible that he really has changed, and he comes across as deeply repentant, seeking salvation first by making himself useful in cleaning the church, and then by seeking to devote himself to Christ. Leung guides him on this journey, but his own path is more difficult, whilst his wife (who never gets a name of her own – one of several small but pointed comments on paternalistic culture) is horrified when she realises what’s going on. With little of her own faith remaining, she feels little obligation to try to forgive.

The film takes a while to get going, then delivers a twist halfway through which is unlikely to shift anyone’s sympathies much, but does invite us to wonder at what attracts moral opprobrium and what is allowed to pass, perhaps, too easily. Questions of what makes us who we are are teased at the start and then dropped – deliberately, one suspects, in order to make us wonder about that later on. Nobody here is innocent; perhaps that ought never to have been important.

The film is generally well put together but the directors’ inexperience shows in the uneven pacing of the first half. It picks up in the second as events built towards a shocking incident that will show everybody clearly who they are. In doing so, this opens up further questions about the relationship between innate character and impulsive actions, and just where culpability kicks in. The film may look simplistic, but with all this under the surface, it’s a satisfying watch. It will be interesting to see what the team can do with a little more experience.

Reviewed on: 14 Nov 2025